The Death and Life of David Scarboro

How Rupert Murdoch’s tabloids drove an antiracist soap star to suicide

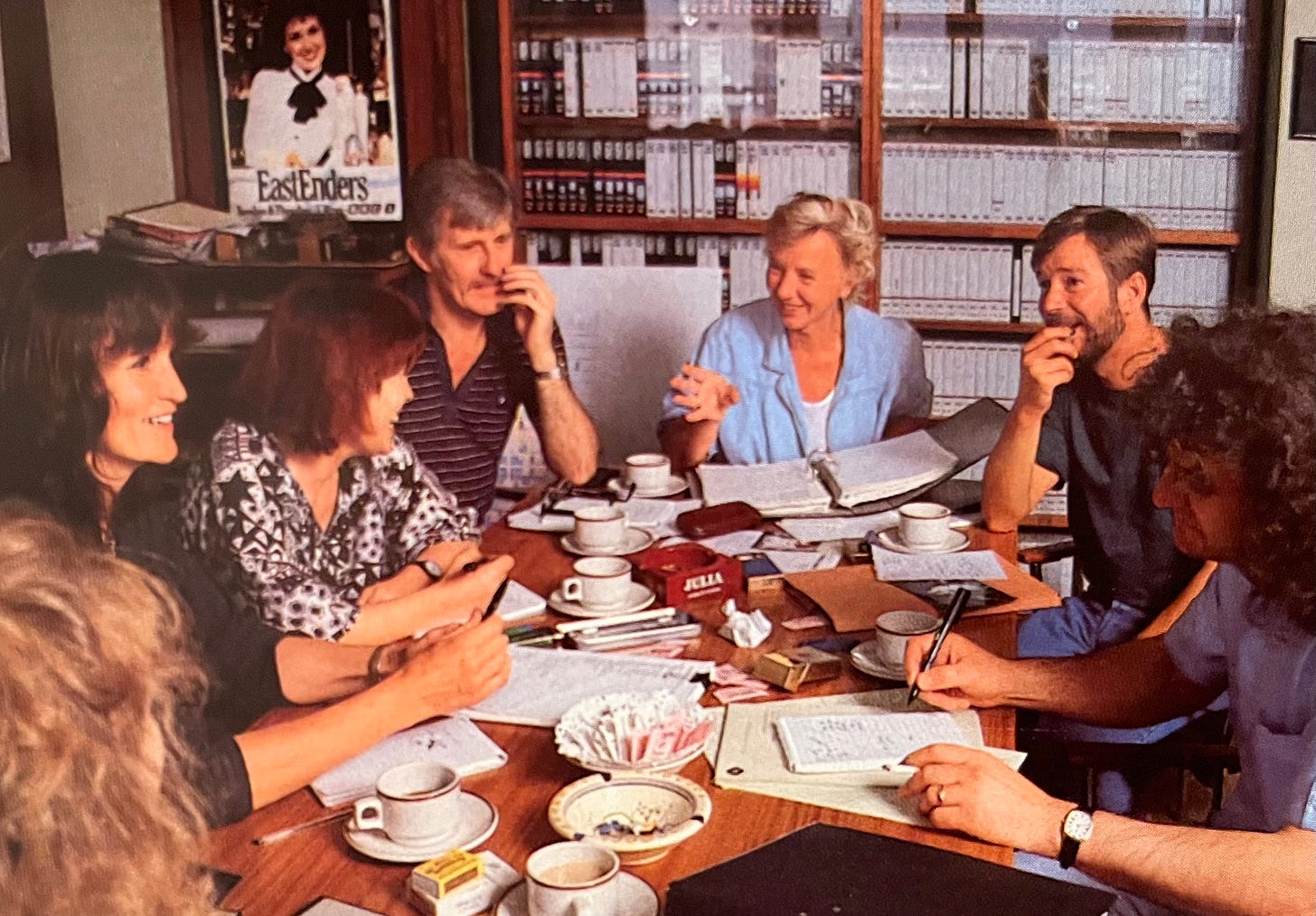

In March 1983, the BBC enlisted Angels producer Julia Smith and her trusty script editor, Tony Holland, to devise a popular continuing drama to match ITV’s Coronation Street and improve its image in the press. Almost a year later, the pair successfully pitched a show about modern life on a Victorian square in London’s multicultural East End. It was to be called East 8.

The BBC had just completed the purchase of Elstree Studios in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, where a forgotten backlot emerged as the ideal location to build a set from the ground up. It was still covered in sand from its most recent incarnation as a Düsseldorf construction site for the filming of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, but Smith saw potential. She picked up a scrap of wood and started to scrape out a diagram of what the square would look like.

“Houses could go here,” she declared. “A central threadbare garden could go there. A pub on that corner. The start of a market next to the pub, and a railway bridge, with a small street connecting them…”

With the set under way, Smith and Holland urgently needed to come up with 23 characters to fill it with, as well as an outline of what they had in store for them over the course of the show’s first three years.

They escaped to Lanzarote and spent the next two weeks frantically spitballing over a typewriter. Holland drew on his own family history to piece together the pivotal clan of the Beales and the Fowlers. Matriarch Lou, inspired by his aunt of the same name, formed the starting point, and then came her 40-year-old twin children, Pete and Pauline, named after his real-life cousins. The Beales and the Fowlers would make up eight of the original 23. Pete would be married to Kathy, and have a son called Ian; Pauline would be married to Arthur, and have a son and daughter called Mark and Michelle.

When the time came to start casting for East 8 – soon to be renamed EastEnders – some of those who got the nod were established actors the pair had worked with before. Bill Treacher, for example, would play Arthur, and Wendy Richard – already a household name since the days of Are You Being Served? – was later cast as Pauline. For others, Smith reached out to agents and drama schools in search of the right talent.

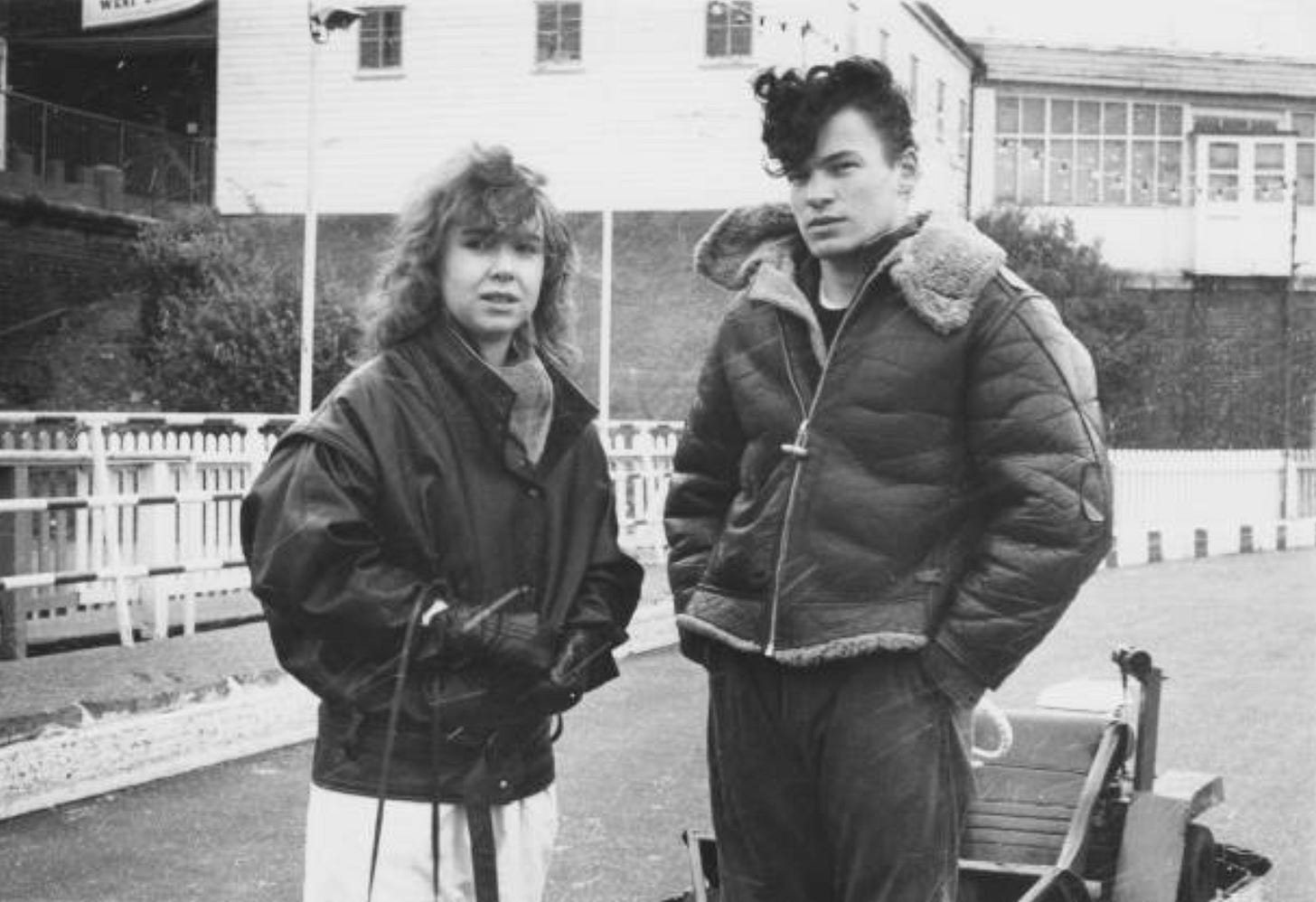

Arthur and Pauline’s children, Mark and Michelle, would both come from Grange Hill stock, albeit with varying pedigree. While Susan Tully boasted the status of a fully fledged series regular, rockabilly David Scarboro had only made a handful of appearances as an uncredited pupil on the teen drama, which despite leading to a starring role in an episode of educational anthology series Scene, meant he remained a relative unknown.

“Several young actors read for the part of Mark, Pauline and Arthur’s son,” it was later noted in EastEnders: The Inside Story, the BBC’s official behind-the-scenes book, published in 1987. “On paper, David Scarboro was the least likely to get the job.

“You couldn’t see much of his face as most of it was obscured by a huge greased quiff that loomed dangerously down over his forehead and threatened to lop-off the end of his nose,” the note continued. “You could see even less of it when he read, because he mumbled into his chest, as if he only wanted his leather jacket to hear the words.

“His eyes were piercing, though, and there was a quality of James Dean about him – the duo reckoned he’d be dynamite on screen. And possibly pretty explosive off, too. He was so like Mark. And complete typecasting could be dangerous.”

One of the soap’s other teen characters would be Kelvin Carpenter. “Paul J Medford was becoming a fixation, as four separate agencies had sent in his picture and details,” another note said. “He was London born and bred and had been a child actor. Good-looking, fashionable and very street-cred – he’d make a good Kelvin.”

With casting complete and the set ready for action, an early 1985 launch date was in sight. EastEnders was about to make overnight celebrities of the likes of Scarboro and Medford, and since the Gods of Albert Square’s fateful fortnight in Lanzarote, much of what came next for them was already written.

“Mark will be leaving school at Easter and is fairly certain to be joining his dad in the dole queue,” they noted. “Mark is a very tough little lad, and at a very dodgy stage in his development ... There’s a kind of amoral streak in his nature ... The area does have a brutalising effect on a lot of its youngsters...”

Another section read: “Both Arthur and Mark are suspects for Reg’s murder. The Fowlers themselves are suspicious of Mark, particularly when they’re also summoned to his school. It turns out he’s been using his school dinner money to buy fags. He gets very friendly with Nick and becomes a skinhead. He’s lectured about associating with Nick and when Nick’s caught it’s likely he’ll be called as a witness. He goes onto a YTS [youth training scheme], dislikes it, gets the sack … Michelle wants to invite [Kelvin] home but Mark’s against it.”

As filming began, Scarboro made a strong impression on Anna Wing, who played his on-screen gran, Lou Beale.

“He had spot-on timing,” Wing recalled some years later. “After the first couple of episodes, I thought he had star quality, and I wasn’t the only one.”

The advent of Scarboro’s first appearance was met with jubilance from his family and the wider community in their local village of Tatsfield, Surrey. “We just sat and watched every second and listened to every word,” his mum, Susan, beamed. “He thoroughly enjoyed it … He’d come home and tell us all about what happened in front of and behind the cameras.”

EastEnders was an instant hit, and Scarboro initially responded to the demands of his busy schedule by lodging with relatives who lived closer to Borehamwood. However, an illness in the family soon meant they could no longer put him up, so the 17-year-old moved in with two friends above a hair and beauty salon in Tottenham’s Northumberland Park.

Scarboro, on the nation’s screens twice a week, started to get recognised wherever he went, and despite his reserved off-screen personality, the tearaway character he played so convincingly planted the seeds of a burdensome reputation. This was only exacerbated the more Smith and Holland’s plans for Mark came into effect, descending from the endearing rapscallion – “I’m on a free period, Gran, honest!” – to flogging stolen goods for Nick Cotton, Dot’s racist, heroin-addict son.

Scarboro nonetheless portrayed Mark’s moral slide in an earnest, sympathetic manner, and it first appeared Smith and Holland were keen to tell the story of a good kid led astray rather than an outright ill-intentioned droog.

But some moments suggested an insistence on taking Mark in the same direction as panto villain Nick. In one scene in the launderette, Mark lays out his objection to Kelvin getting close to Michelle: “Put it this way, Kelvin. Things are being nicked round ’ere. Girls. Our girls. And we don’t like it.”

Scarboro, already struggling with the public’s inability to separate him from Mark, grew concerned as the scripts started to make the character’s discrimination more overt. This eventually came to a head shooting an episode intended to take things to the next stage.

Medford later explained: “We picked up the script on this particular Friday, and we looked through it and we read it, and we read it again, and we thought, ‘Hang on, what’s going on here? No one’s said that he’s going to become a racist’. And, of course, David couldn’t understand why, first of all, or how he was going to cope with it.

“I didn’t have any of the lines to say,” he continued. “I just had to receive the racist attacks and abuse, and David said he wouldn’t say them – under no circumstances – which I found was one of the warmest things someone had ever done for me. He’s actually put his job on the line because he didn’t want to become a racist.”

The resulting scene must go down as one of the most bizarre in EastEnders history, as tight schedules presumably forced everyone involved into rushing ahead with it via a crude rewrite that made hardly any sense.

Mark enters the caff and joins Michelle and Kelvin at a table. After getting nowhere asking his sister for a cup of tea, Kelvin offers to buy him one instead, to which Mark replies, “It’s alright, I’ve changed me mind. I don’t want any now. Not from a United supporter, anyway.”

It appears the writers have hurriedly substituted a racial slur for “United supporter”, which becomes more apparent as Michelle invites Kelvin over for dinner sometime. “A United supporter?!” says Mark. “Dad would go spare!”

It proved to be Scarboro’s last episode as a regular cast member.

“The actor was not happy,” Smith once claimed. “He was a young man only part of the way through the process of growing up, and that process was being severely hampered by the day-in, day-out slog of making EastEnders. The actors have a punishing six-day-a-week schedule. On the seventh day, apart from crashing out, they also have to learn lines for the following week in the studio. David found that he had no time for himself, or for his friends.

“Also, the sudden and unfamiliar high-profile exposure that he was subjected to made him wonder if he had seriously wanted to be an actor in the first place,” she continued. “It had all happened so quickly, and he felt as if he had been taken over. It was sensible that David be allowed to leave the show as soon as possible, so that he could be given the opportunity and the space to sort himself out.

“A break from the frantic round of a bi-weekly drama might help him to decide what he really wanted to do with his life. Maybe he would wish to pursue a career in acting after all, and perhaps he would end up very good at it, time would tell. And if he did opt to be an actor, then Mark could always be brought back into the serial.”

Scarboro’s brother, Simon, understood the situation on simpler terms, having since stated the character’s racism formed the basis of the proposed temporary departure.

Smith could often be brutal in her handling of EastEnders’ myriad moving parts. When once asked in an interview if she ever got tough with her actors, she answered: “Extremely. Yes. One has to be. They have to know. It’s like a child. Actors are wonderful people but part of what’s in an actor’s makeup is a childlike quality … I’m there to encourage, I’m there to discipline, I’m there to bully.”

As for coping without Scarboro, the producer wrote: “The decision to drop Mark presented two immediate problems. One, how was he to be written out? And, two, what would be done with all the scripts on the shelf that he had already been written into? So that the break could be made quickly, the character of Mark was to just disappear. To simply vanish, with no early explanation.”

For the actor, however, his visibility remained painfully acute. Upon Scarboro’s exit from the show, Rupert Murdoch’s The Sun newspaper, then edited by Kelvin MacKenzie, ran a hit piece written by reporter Tim Ewbank.

“Teenage EastEnders star David Scarboro has been sacked from telly’s newest soap opera,” he wrote. “Scarboro, who plays Wendy Richard’s wayward son, Mark Fowler, has been written out of the series after a showdown with producer Julia Smith.”

Scarboro’s dad, Peter, later described the effect Ewbank’s article had on the family. “[David] was hurt for us, and the fact that he was going to have to come back here to live,” he said. “It was a tremendous pressure on him.”

Sylvia Young, Scarboro’s agent and former drama teacher, attempted to get the paper to retract the story to no avail.

Over the summer of 1985, the actor fell into what his brother described as a brief period of alcohol and cannabis abuse. “He still wanted to act, but had lost a lot of confidence,” he said. “He needed money, but there’s not much work in our village, so he went to stay with our uncle, nearer London.”

Things improved for Scarboro in November, when EastEnders got in touch about him returning for some episodes set to air in the new year. “He was really very, very happy then,” his mum recalled. “He was back to his old self, and he was very serious about the work. He really thought it would bring him back into the series permanently, he was really determined to do everything right.”

The Fowlers found Mark in Southend, working on the go-karts in Peter Pan’s Playground and shacked up with a mother of two. The following week, he popped back to Walford to check in on his gran, only to then scarper out the window.

“The Fowler family reunited was big news,” his brother said. “But The Sun and The Mirror went further. Finding out that David was living away from home, they printed these stories…”

“EastEnders boy star David Scarboro sparked off a mystery last night when he claimed he had run away from home – just like his character in the top telly soap opera,” wrote Kevin O’Sullivan and John Askill of The Sun.

“David, 17, who is due back on our screens as tearaway Mark Fowler soon, said: ‘I’ve had a lot of hassle from my parents and I don’t like them. I’ve been living with my uncle and I’m very happy. There’s no chance of me going back.’”

Ronald Ricketts and Edward Vale of The Mirror – owned at the time by Robert Maxwell and edited by Richard Stott – ran something similar.

“Both stories were completely untrue,” said Scarboro’s brother. “The newspapers seemed to be wanting to make David the same as Mark.”

His dad recalled: “He came back on a Sunday and was sitting down, and he literally cried, saying, ‘I’m so upset, ’cause I didn’t say that. You know I didn’t say that.’”

Scarboro tried to push on nonetheless. In the spring of 1986, he moved back into the family home and worked part-time fitting carpets until he got the next call to appear on EastEnders, this time alongside a strange Welsh sidekick with a passion for marrows, Pink Floyd and weed. And yet, no offer of a permanent return arrived.

Typecast as Mark Fowler, Scarboro lost faith in the chances of landing another acting job. His friends described him as becoming withdrawn and paranoid, which by 1987 had worsened to the point of clinical depression. Scarboro’s family intervened, and he agreed to check into a psychiatric unit.

“After a couple of days ... he received a message to phone a girl,” his brother said. “He phoned, and after chatting for a while, he realised he was talking to a reporter from The Sun. They’d tricked him.”

Ruki Sayid wrote: “Tragic EastEnders star David Scarboro was in a mental ward last night after suffering a horrifying bout of depression.”

With the location of the facility exposed, Scarboro’s treatment was made impossible, and he had little choice but to check out before the reporters arrived.

His mental illness remained untreated, but he once again took up EastEnders’ offer to pay a fleeting visit for Christmas Day 1987. According to his mum, “He said, ‘well, it doesn’t mean anything because so many times I’ve thought something’s gonna come of it…’ So he just went and did the episode, and he was quite prepared just for the one episode ... I don’t think he really enjoyed that one.”

Scarboro attempted suicide over Christmas, and his recovery was constantly disrupted by Murdoch’s News of the World. With the blessing of then editor Wendy Henry, reporters hounded Scarboro for an interview, and threatened to print a story about him taking drugs if he failed to comply. His agent refuted the accusation, and reminded the paper her client was “very sick, and not in a fit state to do any interview”.

The press then resorted to parking up outside his family home and dropping in on the village corner shop and pub in search of whatever tidbits they could find. Scarboro’s brother even recounted telephoto lenses being pointed at his window for two weeks straight.

At the end of January 1988, Tim Carroll of the News of the World wrote: “Tearaway EastEnders actor David Scarboro tried to kill himself in despair at his flagging TV career and turbulent love life.

“Weirdo David, 19, who plays Pauline and Arthur Fowler’s mixed-up son Mark, scribbled a suicide note in an all-night drink and drugs binge in his bedroom at his parents’ house.

“Now David, who has blown his chance to stay on EastEnders after a series of bust-ups with producer Julia Smith, is back home,” he went on. “He was kept in hospital at Bromley, Kent, for 24 hours.

“He is known as Dracula in Tatsfield because villagers claim he is white as a sheet and only comes out after dark,” wrote Carroll.

As promised, the paper also went ahead with the drug angle. “Pals say he has taken cocaine, but is now fighting the problem which wrecked his dream of success on the BBC soap,” the article continued. “Loner David’s only mate in Tatsfield, pop group road manager Nigel Dean, confirmed that David did have a drug problem. Nigel said: ‘He was into coke quite badly last year, but he’s dragged himself out a bit.’”

Nigel Dean, merely an acquaintance from the village, swiftly reached out to Scarboro to repudiate his alleged corroboration.

Scarboro’s girlfriend of 18 months insisted he never took any drugs during that time, and his doctor from the psychiatric unit attested that he had witnessed nothing to suggest he was on any illegal substances during their sessions.

The actor commenced libel proceedings against the News of the World, and his solicitor set about compiling testimonies from everyone the press had claimed to have spoken to. One by one, each individual dismissed the quotes that had been attributed to them as lies, but on 27 April 1988, before the case could reach court, Scarboro died of suicide. He was 20 years old.

In March 1989, Simon Scarboro presented a Scene documentary about his brother’s life and the role the tabloids played in his death.

In November 1989, Wendy Henry was fired from her next job as editor of the Sunday People for publishing a front-page photograph of seven-year-old Prince William urinating in public.

In August 1990, Mark Fowler returned to Albert Square, this time played by Todd Carty.

Despite the likes of the 1993 Calcutt Report and 2012 Leveson Report, the UK remains in severe need of a free and accountable press. Campaign group Hacked Off’s website reads: “In March 2013, the three main political parties supported the implementation of Leveson’s reforms, and so did the public. In fact, more than 175,000 people signed our petition calling for immediate implementation.

“Press abuse continues, and in the place of the PCC, the majority of newspapers in the UK are ‘regulated’ by another toothless complaints-handling body, IPSO.

“We are committed to holding power to account and building a press which works for everyone.”

David Scarboro should be remembered for his charismatic, often gentle performances as the original Mark Fowler; as someone who stuck to his principles, and in doing so steered the character far enough from depravity to lend credence to his eventual redemption.

“He was a good actor,” said Medford. “He was acting. And that’s something that the press and the audience failed to see.”